This is a piece from my newsletter, (me + you), which comes as the spirit moves but is hopefully worth the wait. I use it as a place to test drive ideas, to practice therapy, to get writing tics out of my system…it’s really just a sandbox for me to write to you. The newsletter is about everything and nothing, and this one is about a trope I enjoy a lot. I wrote this back in October and it’s posted here pretty much unchanged, save for one dumb joke I added for the die-hard fans. You can stream Cucuruz Doan’s Island now, so go check that out.

Despite the fact that it was commissioning a murder, the ad didn’t feel creepy, but was rather streamlined, with a modern feel. It had quite a lot of visual impact. A considerably skilled designer must have been hired for the purpose.

–Kazuhiro Kiuchi, Shield of Straw

—

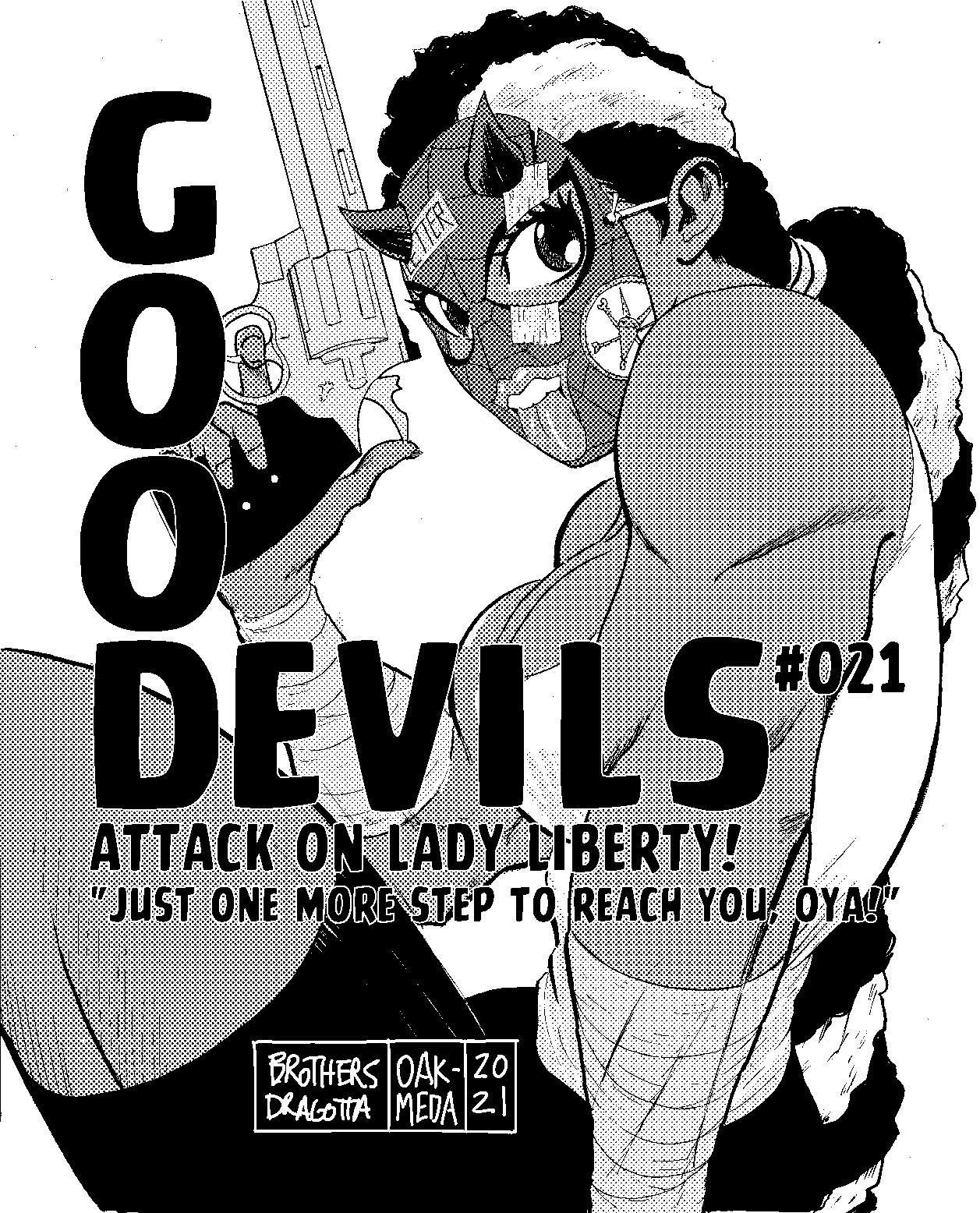

I’m a fan of killers with rich home lives (Nobody trailer), hitmen with loving relationships that take them out of the game (John Wick trailer), and assassins who demonstrate compassion for the vulnerable (Kate trailer). I love this stuff in movies, even if the actual movies end up being so-so. In non-Genre Wick movies, think of The Professional or characters like Wolverine, gruff dudes who kill people and raise daughters. There’s also criminals who operate orphanages, a go-to trope for yakuza (and plot point in the Yakuza video game franchise, which stars a nigh-virginal and nigh-invincible career criminal, who is also a valiant protector of the needy).

It’s a fun trope because these characters are attempting to reconcile the troubled lives they live, whether they create the trouble or have been subjected to it, with the peace or love that they’ve grown to enjoy or aspire to receive. It’s very relatable, very clean. It’s the kind of thing we’d talk about in therapy, only for us it’d be a square job, rather than shooting people and having great abs. The addition of a crime or some type of transgressive or troubled aspect to a relatable feeling like this turns it into an interesting moral quandary when I mull it over; a suggestion of where a person’s values may truly sit, even if their actions temporarily indicate otherwise.

Basically, we’re all capable of being good, deep down inside, right? It’s just that sometimes you have to dig for it. It’s not innate. It takes work. Movies like this hint at the work or demonstrate one way it may go in a way that I dig.

—

There’s another trope, a cousin to the temporarily well-adjusted killer thing, that’s come up in a few different stories specifically from Japan that I’ve enjoyed, most recently the movie Mobile Suit Gundam: Cucuruz Doan’s Island, directed by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. In it, the mobile suit pilot Cucuruz Doan deserts the military after witnessing the toll war takes on a bunch of children he’s implied to have orphaned during battle in particular. He settles on an island with a frankly untenable number of teens and toddlers for one man to raise. He teaches those orphans how to live well, repair things, respect each other, and grow their own food. Their life is complicated when Amuro Ray, the ace pilot and original hero-star of the series, ends up stranded on the island and must learn to work alongside them, despite being on opposing sides. There’s a big focus on working with the land, Amuro and Doan both, as a way of implicitly cleansing themselves of what’s required in the war outside the island.

A similar scene popped up in Takehiko Inoue’s comic Vagabond, the story of how Miyamoto Musashi became the greatest swordsman of all time. After killing dozens upon dozens of men and repeatedly proving his prowess to every person with a blade that was fool enough to cross his path, Musashi was left depleted and overwhelmed by the weight of living amongst so much endless death. While wandering, he comes upon a small village that’s surviving on the edge. He settles there, learns to till the fields and even how to tell different types of dirt apart while helping them with planting, and eventually, he discovers a new way of being himself, a revelation which in turn will push his swordsmanship to a new level.

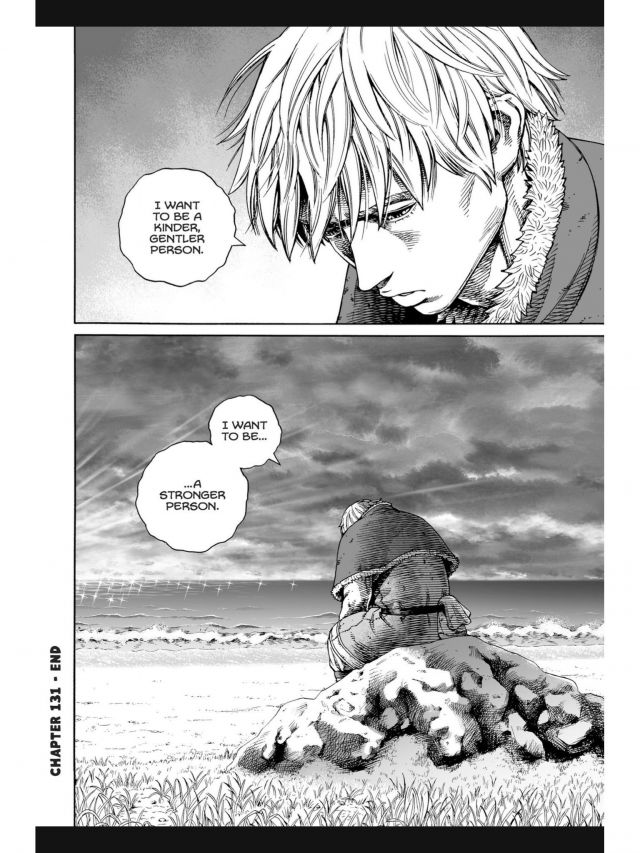

In Makoto Yukimura’s Vinland Saga, young Thorfinn forges himself into a blade, a ferocious fighter with a knife in each hand that’s desperate to avenge the death of his father at the hands of his current employer some years ago. Much later in the series, once that plot has run its course, we meet Thorfinn again as an adult. At this point, for a wide variety of reasons, he’s given up violence as a way of life and settled into serving as a slave for a landholder. He shows no real intentions of escaping even. He’s found a place and he’s found a measure of peace, not in service, but in deepening his connection to the ground and his community. He fears returning to boy he was, which speaks volumes about the man he’s become.

In Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time, written and directed by Hideaki Anno, Shinji Ikari and Rei Ayanami are two children who have spent their adolescence fighting against giant monsters for the sake of humanity, only to see most of the population of Earth essentially culled via horrible conspiracy. While their fellow frozen-in-time teenage warrior Asuka Langley has had fourteen years past her debut to learn how to cope with the ongoing apocalypse, these two are lost, figuratively adrift. They discover their innate humanity, thriving culture, and local community by working the rice paddies with the locals.

The discovery is part of a long sequence, a mix of still shots and exquisite animation. You see Rei Ayanami getting closer to her neighbors, learning the vagaries of the land, and opening up. Her plugsuit forever represents the gap between her and the rest of humanity, the difference between them, but it isn’t a wall. It’s not a cage. She’s here. She’s us. I like this compilation of her being curious about life.

—

A brief sidebar, because I want to say this but don’t have an essay in me about it: part of the joy of mecha animation is being at the human scale looking up at the robot, or being at the robot scale and marveling at the small figures below. Anno and company take Evangelion 3.0+1.0‘s POV and aim it squarely at the eyes of the people living under the feet of giant robots for a great deal of the movie. It feels like an emphatic message, as if Anno’s saying, “I know you came here to see beautiful robot fights, but look at these lushly animated moments of simple life. Look at a mother breastfeeding, think about what it means to say ‘good morning’ to someone you love. The robots are cool, but they’re just a vehicle for this: I’ve been depressed. I know despair. But I love my wife.”

It’s a good movie. The fact that the trailer ends with Utada Hikaru singing, “I love you more than you’ll ever know” on “One Last Kiss” feels remarkably significant.

—

Each of these works were produced over years and far apart from each other. They’re not directly related, other than sharing a language and I guess being composed of millions of little drawings. The lines I draw between them have me at the center, you know what I mean? The main thing they have in common is that I found the latter three greatly moving when I encountered them, which was also exactly when I needed to encounter them each of them emotionally. (Sometimes it takes a few tries before you really get it.) When the trope popped up in Cucuruz Doan’s Island, I found myself immediately charmed by the movie and curious to see where they’d take it. “Oh, it’s gonna be one of those, huh?” as I lean forward in my seat.

This is a trope that works very well on me, something I recognized in my self thanks to those three projects. It works because there’s something about the tactile aspect of the emotional metaphor and physical actions they take that feels familiar and intensely relatable. Growing up, my grandfather had me helping out on the various projects we had going around the house, whether that was sorting out whatever was clogging the septic tank, yard work, or cutting down trees. It was a pain at the time, because we generally did all this during the exact duration of the Fox Kids Saturday morning cartoon block, but I grew to enjoy it over the years. It gave me a work ethic I’ve carried into adulthood. A job’s not over til it’s done, in a work now, party later sense.

Yakuza operating an orphanage or hitmen getting married are kind of the vibes-y version of this kind of emotional and cultural reconciliation. Most orphanages of this type in media are run by like, a handful of colorful characters, their ingenue daughter who is probably gonna get kidnapped at some point but she’s a scrapper so it’ll turn out okay, and the thirty-six thousand cartoonishly cute children who live there. There’s a level of unreality that doesn’t harm it, but doesn’t necessarily help me see my self in it either.

Here: Cucuruz Doan somehow provides food for a dozen mouths on an island that appears to be mostly rock and the remains of the giant robots that he goes out and fights to protect them. “You wanna know how do I provide for the kids, man? The minovsky particles provide, brother. The minovsky particles provide.” That’s what I mean by vibes-y. You’re not supposed to scratch this surface.

But the planting stuff, digging and working with your hands and finding a measure of peace doing it; I’ve been fortunate enough to do some of the things in real life that these characters simulate on-screen or on-panel, so the resonance I feel there is sometimes very strong. It makes me snap to attention to see if what they get out of it is what I get out of it.

—

I think my favorite thing I did as a kid out in the yard was help tear down a brick fence with a sledgehammer. We needed to put down a new wooden one a few feet further out, so me, my grandfather, and my uncle went outside. They handed me a sledgehammer, which I was barely big enough to hold at that point, and I gave the fence a good swing. It blew a relatively small hole in the front of the bricks for the size of the head, which was disappointing at first. But then I realized that the hammer had absolutely exploded the back side of the fence in a shower of orange and white. It ruled, honestly. Demolition is rough on the hands but great for the soul.

—

The crux of it, the engine of these stories for me, is an emphasis on the literally physical aspect of working with the land, and what that may result in emotionally. Characters pick up clumps of dirt, they learn how to work a rice paddy, and—a personal favorite—how to dig effectively. They get their hands dirty, and that provides the connection they need to discover or rediscover their humanity. They stand side-by-side with their peers, even if they don’t realize it or acknowledge it yet, and learn what it’s like to belong, rather than being the best, or the hero, or lost.

These men and women all learn different, story-specific things from their farming and found family experiences. The stories have a similar engine and similar ideals, but those similar ideals are put toward myriad ends. Maybe the lesson is that you can’t be a warrior and a farmer due to a core incompatibility between the two, or maybe it’s that a sword swung for no reason but pride is a cosmic waste. For me, beginning to get a handle on my feelings was aided by an approach to perspective I’ve been summing up as “Some things matter, most things don’t” for years now, because while I occasionally can’t be emotionally honest with myself, I can always be ruthlessly glib. It’s true, though.

Within this trope, everyone involved gets to where they need to be via the same route, which is changing their focus and humbling themselves—that is, stepping away from their all-consuming mission and submitting to something greater than their ego, their self. They’re submitting to us and our needs, and I don’t mean “us” in the sense of “us versus them,” but “us” in the sense of “us and them.”

They’re we and we’re us. This trope feels like an implicit step away from Lone Man or Chosen One-type stories, where only someone special enough to beat the local menace or destined to be here can save us, and toward something focused a little more on community. You need to be part of us to save us, maybe. It’s easy to lose sight of that in stories, which sort of require someone to be set apart and focused on to the exclusion of others. But in real life, it’s not the same way at all, is it? It’s nice to see stories that nod in that direction, even if they do tend to universally end up in a one-on-one fight because the genre demands it. That’s cool too, I think.

—

Lately, I’m watching Island of Sea Wolves on Netflix, this behind the scenes video showing how they did a neat stunt from The Raid 2, this wrestling match from TNT Extreme Wrestling Supreme Extreme 2019 featuring Vancouver’s own El Phantasmo versus Death Triangle’s Rey Fenix doing some wild anti-gravity stuff in the ring, and I’m finally a couple episodes into the second season of The Sopranos. I’ve been alternating listening to Ari Lennox’s new and extremely nsfw album age/sex/location (“Hoodie” music video, cold showers to your left) and the new Yeah Yeah Yeahs record, Cool It Down (“Spitting Off the Edge of the World” music video).

Speaking of the varying morality and connections in crime movies, Michael Bay’s Ambulance is about two brothers (no relation) who rob a bank together and then have to escape from the cops. It’s a movie that has almost everything I like in crime movies, so it’s possible I’m a bad judge, but I really enjoyed it. (There was no gardening, though). What really killed me though is that Jake Gyllenhall has a line in there toward the end about the difference between his brother and him that made me lean back and realize I’m gonna be thinking about this movie all year. If you’re open to Bay, it’s a barnburner.

thanks for reading,

davidb