This is a piece from my newsletter, (me + you), which comes as the spirit moves but is hopefully worth the wait. I use it as a place to test drive ideas, to practice therapy, to get writing tics out of my system…it’s really just a sandbox for me to write to you. The newsletter is about everything and nothing, and this one is about how I felt before, during, and after watching Takehiko Inoue’s The First Slam Dunk. I wrote this back in January, shortly after seeing the movie in Japanese sans subtitles and after a season of bad brain days. Memoir as criticism, I guess. The First Slam Dunk is a great movie, and the art book is pretty cool, too. I saw the English dub today, which is as good a reason as any to make this public.

“Top priority:

Peace before everything, God before anything

Love before anything, real before everything

Home before anyplace, truth before anything

Style and state radiate, love power slay the hate”

–Yasiin Bey, fka Mos Def, “Priority”

Back when I was first learning how to read, I used to do this one thing that was great for me but terrible for my aunts and uncles. They were nine or more years older than I was back then, so firmly in their teens and early twenties. Whenever we watched a movie, I’d demand to watch the credits to see if I could find my name, and, being one of the babies of the family at that time, I usually got my way. I was learning to read, and since David is an eternally popular name (with good reason, beloved), I knew my name would be in there somewhere. I just had to sound every other name out to find it.

So I’d read all the credits to everything we watched while my aunts and uncles were desperate to change the channel, to leave the theater, to simply get on with things. I’d even get upset when tv shows do that fast credit thing to get to the movie up next faster. I’d read all the jobs and names in my head as the credits ran, even though I didn’t understand many of them.

I still do this as an adult, and since Marvel’s movies made it cool, my friends get it too.

On New Year’s Eve just past, I was sitting in TOHO Cinemas Nihonbashi in Tokyo about fifteen minutes before the year turned over. I’d just finished watching The First Slam Dunk, the adaptation of Takehiko Inoue’s classic boys’ sports manga written and directed by the mangaka himself, and the credits were rolling. I don’t read Japanese well yet, but I wanted to see if I could read some of the kanji and see how many names I could read and roles I could sound out. I’ve been studying Japanese off and on for the past few years, never quite as seriously as I should be considering my day job is in localization, and this was a good way to test my reading after a whole movie’s worth of listening practice.

On New Year’s Eve just past, I was sitting in TOHO Cinemas Nihonbashi in Tokyo about fifteen minutes before the year turned over. I’d just finished watching The First Slam Dunk, the adaptation of Takehiko Inoue’s classic boys’ sports manga written and directed by the mangaka himself, and the credits were rolling. I don’t read Japanese well yet, but I wanted to see if I could read some of the kanji and see how many names I could read and roles I could sound out. I’ve been studying Japanese off and on for the past few years, never quite as seriously as I should be considering my day job is in localization, and this was a good way to test my reading after a whole movie’s worth of listening practice.

I thought about being a kid and doing this same thing thirty-five years ago maybe and laughed a little. I thought about becoming a comics critic as an adult and how important proper credit eventually became to me. Getting the names right centers that fact that whatever thing was made by human hands in my head. “If you do it, it’s yours and you deserve the credit.”

It’s less a line drawn from childhood to adulthood so much as two parallel lines, two ways of looking at one thing. I didn’t have the capacity to understand the importance of artistic credit as a kid, right? But as an adult, reading credits is like looking at a long list of people who’ve earned being credited their work, even if I have no idea what their field is all about. “We made this.”

On “RAP Music,” Killer Mike says, “I’ve never really had a religious experience in a religious place. Closest I’ve ever come to seeing or feeling God is listening to rap music. Rap music is my religion.”

I’m a little similar to Killer Mike here. I grew up in the church and I still practice/believe, but I don’t go to in-person church for various reasons. But I do appreciate and desire the presence of the sacred in my life, and the way I experience my connection with the sacred more often than not is through creation of my own and through seeing the results of someone else’s thought and effort.

I don’t know if you feel similarly, but I absolutely love to see people cooking, just killing it at whatever they do. Whether it’s Steph Curry draining threes from unlikely distances and angles or Kim Jung Gi effortlessly drawing a whole piece freehand, I love when there’s something there that makes me pause and go, “Man, humans can do that?” It’s that hashtag blessed to be here feeling, but overwhelmingly earnest.

I’ve talked about this a fair amount on our podcast Mangasplaining, but there is a real pleasure in reading a book by someone who loves to draw, rather than someone who just uses comics as a vehicle for the story (non-pejorative; sometimes you need a certain box to carry a certain idea), and a special pleasure in seeing the figurative hand of the artist behind the work. I recognize that hand most often in how “drawn” something feels, how well I can see the seams and imperfections that come when humans do anything. The emotional resonance that they pour into the work matters a great deal too, (said the critic, shuffling towards legitimacy), but give me a scratchy, uneven human line over a cleanly machined one any day of the week. Clean drawings are nice, but there’s something fresh about the other.

It’s like songs with dirty drums. Clean drums are great, but dirty ones just hit different, especially in a car. Sometimes the imperfections of the process become a bonus feature of that process, and that’s something you can really fall in love with. This is as true of art styles as it is music production. The idiosyncrasies are the best part.

I don’t know the meaning of life, what God specifically wants me to do on Earth, but my best guess is that simply living it, taking care of each other, and doing things we love is gonna get me pretty close to the target. When I see someone excelling at their craft in a certain way, I feel second-hand enthusiasm. It makes me think that they’re feeling it, that they’ve gotten in touch with something that has then gotten in touch with me. It feels amazing, experiencing things like that. It feels sacred. I’m frequently flooded with gratitude when I find something that hits the right spot.

I feel it directly when I’m writing. There’s this bit in the war movie Fury I dig a lot, when the character Bible is complimented for some good shooting, and he says, “I’m the instrument, not the hand.” Flip it to “I’m the bullet, not the gun,” and you kinda have how I feel about a lot of things. I haven’t aimed myself or placed myself anywhere. I’ve gone where I’ve been sent and met whatever was there for me head-on, to the best of my ability, and in doing so, hopefully revealed my own nature to my self.

Nothing feels as good as sitting there with a blank page and filling it line by line, crystalizing my thoughts one after the other and making them readable for someone else, even if there’s no intended audience for whatever I’m writing. When it’s pouring out of me, I know that I’ve found something inside myself that I needed to say. When it’s dragging, I know that I’m not writing the thing I need to write at that particular moment in time, like I haven’t given the idea enough time in the metaphorical oven to crystalize it just yet.

Realizing that I feel better when I’m writing regularly was a big surprise. I didn’t recognize the meditative aspect of a regular writing practice, for lack of a better phrase, until I hit a period where I wasn’t writing and getting used to a new gig and felt off in a new way. When I came back, it felt like coming home.

Nowadays, I keep a few projects in progress, and this newsletter is my “long-term” one. I do it as needed…I hesitate to say “as the spirit moves,” but it’s not not that, either. I don’t wait for inspiration, but sometimes something settles on my heart and is like, “Yo, get me on a page somewhere quick.” Sometimes the idea itself is banging on pots and pans, hollering about finally being ready to go. (That’s where that Gundam fanfic I wrote came from.)

I’ve been writing comics for a couple of friends (an unexpected development, but welcome) and doing a little prose fiction for myself for a long while now. I figured out what I want from my creativity and I think I’ve found solid ground to stand on. I want to be better than I am, but I’m happy with where I’m going, too.

(I don’t have the heart for the full freelance life, though. Chasing invoices was stressful enough to me that even if I’m on vacation from my day job, if I know one of my freelancers has an invoice coming, I’ll file that from wherever I’m at.)

I’m not sure where writing will take me, but I don’t know that it needs to take me anywhere. I do what I want, it feels good, and sometimes people say nice things about it, too. It would be nice to get rich off words, but that’s a long shot. I’m happy doing what I do, and challenging myself when I can.

In John Rambo, a fairly execrable movie, Stallone says that “When pushed, killing is as easy as breathing.” Love the line, don’t care about basically anything else in the movie, except for a gnarly mounted machine gun bit at the end. Anyway, I’ve been stealing that to describe how writing feels for years. “Writing is as easy as breathing to me.” It’s how I process things. Writing well? That’s a little more complex, of course.

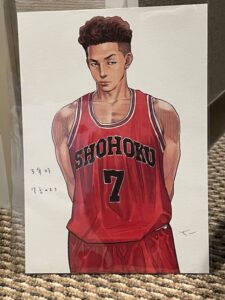

How was The First Slam Dunk? My spoiler-free take is that it is a comic book movie that would be delighted if you read the comics. There are multiple moments where you can see Inoue’s hand, not just as director, but as the original artist. It’s explicit about its origins, about the fact that someone sat down and drew a couple dozen volumes of basketball action with his own human hand.

How was The First Slam Dunk? My spoiler-free take is that it is a comic book movie that would be delighted if you read the comics. There are multiple moments where you can see Inoue’s hand, not just as director, but as the original artist. It’s explicit about its origins, about the fact that someone sat down and drew a couple dozen volumes of basketball action with his own human hand.

It’s beautiful in a way I wasn’t expecting at all. I’m not really into the 3DCG side of anime. Mostly, they make me want to read the comic because the visuals tend to be lackluster compared to that raw uncut stuff that I love. But Inoue is so present here that the texture of the thing actually feels good. It made me want to reread the comic because it’s a testament to that work. Having Inoue behind the camera reinforces his POV from the original work, but now with the presence of thirty-some years of hindsight and frankly explosive artistic growth. There were multiple moments where I knew exactly what was about to happen, and yet it still hit me like a ton of bricks. I was vacillating between being fully in my feelings while watching and being fully wrapped-up in the world of the film.

It’s a couple hours long, and the majority of it is an adaptation of existing material, with the addition of several new scenes to further flesh out the original work. I watched it in Japanese sans subtitles and understood maybe a fifth of the dialogue in real time, but, having read the series a handful of times, I know the comic well enough that the other four-fifths was still familiar in the moment, and I got the rest via context. (Slam Dunk is an all-timer. A lot of what made Haikyu!! so good feels like a response to Slam Dunk.) I was crying by the end of the movie, even with the language barrier.

—

I crystallized the idea that led to this newsletter while watching it. I took a trip to be anonymous and out of my head for a while. I had a year that felt like it sapped my motivation despite having a number of true highlights that I appreciated. I wanted to be alone with my thoughts and out of my routine, but not so far out of my element that I’d feel uncomfortable and be unable to focus. I’ve visited Japan a number of times now and my Japanese is finally strong enough for a solo trip, so I went for it. When I saw that The First Slam Dunk was still in theaters, I took it as an opportunity to watch a movie that at worse would remind me of something I liked and then greet the new year ten minutes later on the walk back to the hotel, just me, my self, and I.

I’d been thinking a lot about the sacred and my connection to it before the movie. I love the idea of ecstatics, people who’ve given themselves body and soul to art. It’s not quite my relationship to art (I was never really a speaking in tongues guy, either), but when I’m feeling low, art is what I tend to turn toward when I need something to smother a bad brain day.

I was thinking about ways to reinforce my connection to the sacred and steal back some motivation when I sat down. About ten minutes into the movie, I had my answer. I realized that Inoue was cooking, and cooking in a way that felt custom built for me.

He was cooking cooking, like that ten-minute Black Thought freestyle. That thing in him that led to Slam Dunk in the ’90s reached across the years to find him once again, resulting in something new and wonderful. And then that new thing enveloped me in a theater an eleven hour flight from home and a sixteen hour flight from where I grew up, and found me too.

I felt what he was putting down, and the way he put it down demands more from me as an audience member and a person who writes things. It made me wanna really shake some confidence issues I’ve been working with and get back to being dangerous. If he can do it with his own human hands, and art and culture is achievement stacked on achievement on achievement, then I have to build from this new foundation he’s shown me. It made me want to be better. You must aim this high to ride.

The First Slam Dunk is a proper sports movie. It’s the exact kind of achievement that makes me feel grateful to God for letting me and Inoue share the same time on Earth. I could’ve been born at any time but I’m right here, right now, watching a basketball movie based on a basketball comic that’s making me think about how much I love my mom in the middle of one of the most awe-inspiringly dense cities on Earth. That level of depth makes me feel like there’s something bigger than us that connects us all.

Thanks for reading,

davidb